By FUTUR team

2022 DEC

Are Garden Cities the new Regenerative Communities?

Are Garden Cities the new Regenerative Communities? We here at FUTUR definitely hope so! Creating a Regenerative Future through the building of Regenerative Communities is a welcome step in the right direction.

Learn more about this topic, its history, prospects, and possibilities in the article below, written by Amanda Kolson Hurley for Foreign Policy.

The machine is a gardenOriginaly published on Foreign Policy by Amanda Kolson Hurley

In 1898, an unassuming British stenographer hatched the idea of "Garden Cities" as an antidote to dirty, crowded London. Today, a revival of that idea is spreading from the U.K. to China to India-and some people think it just might help save the planet.

On 71st Avenue, just south of Queens Boulevard, in Forest Hills, New York, there’s a small shopping strip that looks like countless others in American cities. Banks, shoe stores, and delis sit side by side, recalling a time not so long ago when going shopping meant more than a trip to Target. But keep heading south, crossing under an elevated railway, and it feels like entering a different kind of time warp: Abruptly, asphalt becomes brick and spills into a broad, sunny square. Red-tiled, half-timbered buildings suggest an Italian piazza by way of medieval England. Shady sidewalks curve away from the square. The only reminder that it’s the 21st century, and that this is New York, is the rumble of a train on the Long Island Rail Road overhead.

This sense of being in a city, but not of it, is precisely what the designers of Forest Hills Gardens intended. In 1909, after buying 142 acres of open land, the Russell Sage Foundation hired architect Grosvenor Atterbury and landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.—son of Central Park’s famous creator—to build a model suburb. It was to be an example of the new developments that the explosion of railroads and streetcars were producing, a place that combined the best of town and country. For inspiration, Atterbury and Olmsted looked to a new trend in England said to offer just this kind of mix: garden cities.

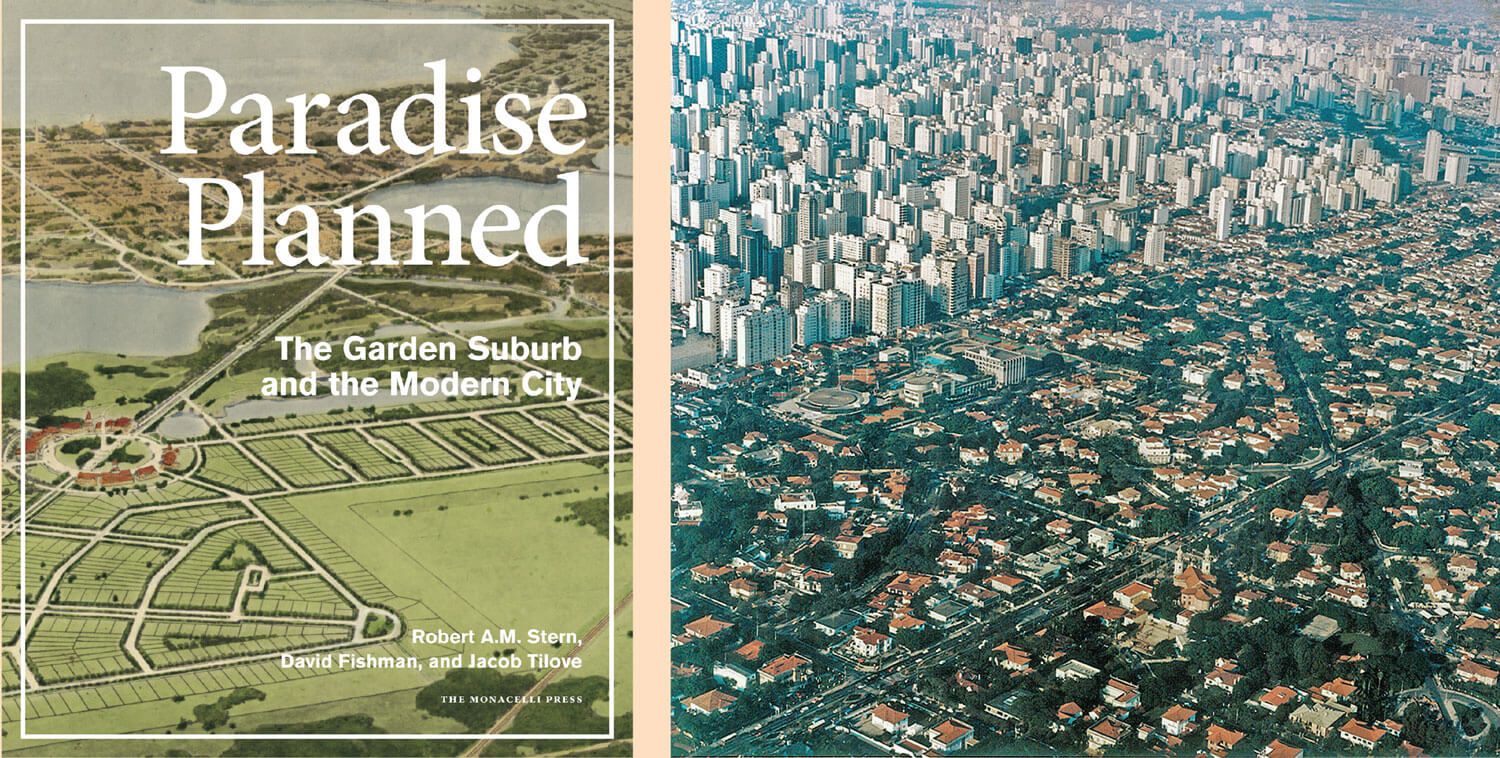

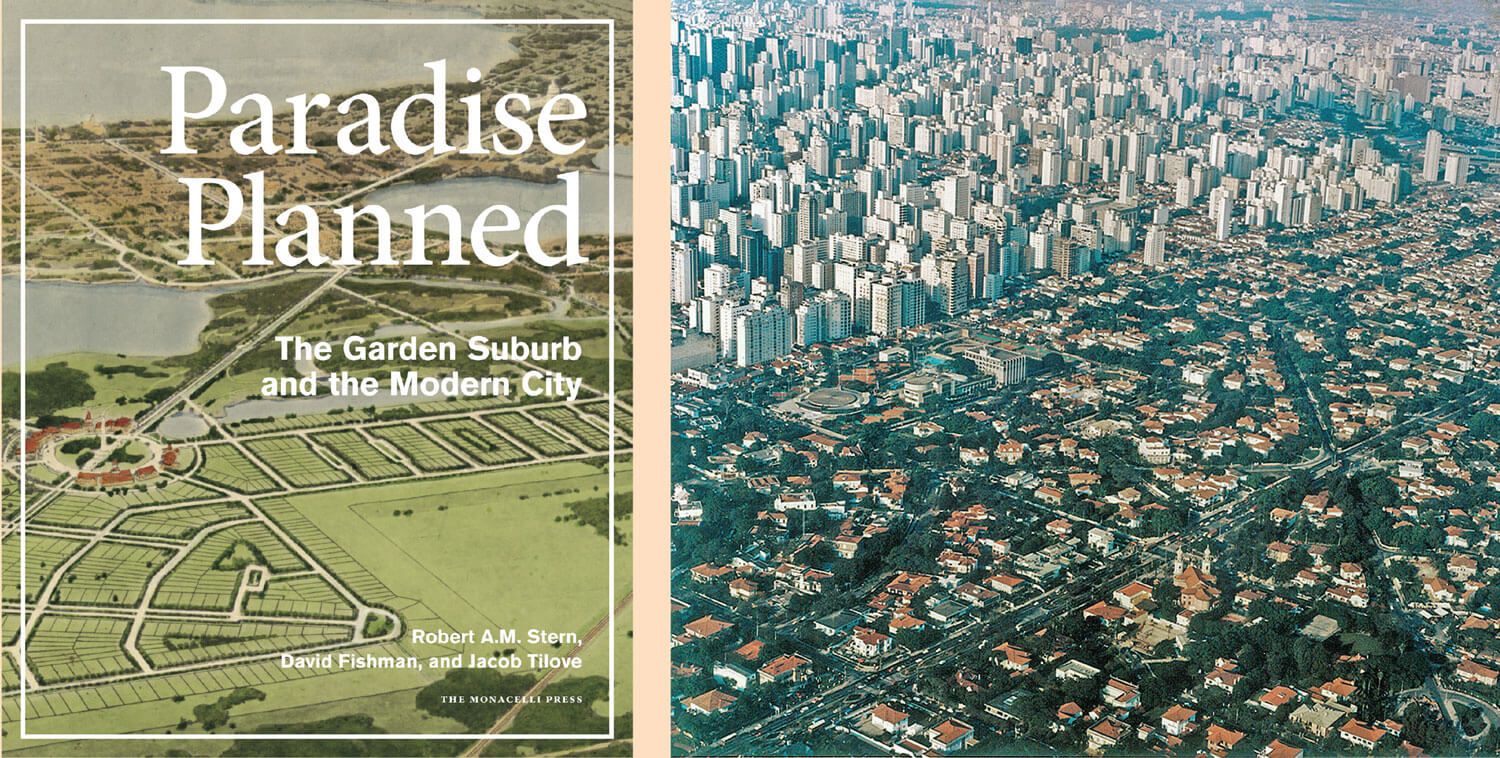

The concept of the garden city was devised by 19th-century social reformers to offer everything big cities didn’t: a limited number of residents with ownership over their community’s land; spacious, well-built homes for people of diverse means; clean air and ample green space; and centers of employment, education, and culture that could easily be reached on foot. Its slightly younger sister, the garden suburb, took the garden city’s basic features—residential streets gracefully enfolding a central avenue or green—and transplanted them to the outskirts of urban centers. The idea caught on across England and in numerous other countries; after Forest Hills Gardens, for instance, came the chic neighborhood of Jardim América in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 1913, and Denenchofu, a Tokyo suburb, seven years later.

After a few decades in the limelight, garden cities fell out of fashion. But recently, they’ve been making a comeback. A small but growing number of architects, urban planners, and policymakers are holding up garden cities as potential antidotes to everything that ails the modern city, from substandard housing to environmental degradation to the segregation of rich and poor.

Among these proponents is Robert Stern. In December 2013, Stern, the dean of the Yale School of Architecture, and two co-authors released a book called Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City. At 12 pounds and some 1,000 pages, the book is bursting with photographs, drawings, and plans that chronicle the long tradition of the garden city and suburb, including Forest Hills Gardens. Yet the book is not just a history, the trio writes: It offers “a development model for the present and foreseeable future.”

The stakes of finding such a model to guide urbanization are high. By 2030, 1 billion people (nearly one out of every eight on the planet) will live in Chinese cities, and Indian cities will swell with about 200 million new residents. Meanwhile, the specter of climate change hovers over all cities, which account for up to 80 percent of greenhouse gas emissions and are especially vulnerable to air pollution, heat waves, and wind and flooding brought by storms.

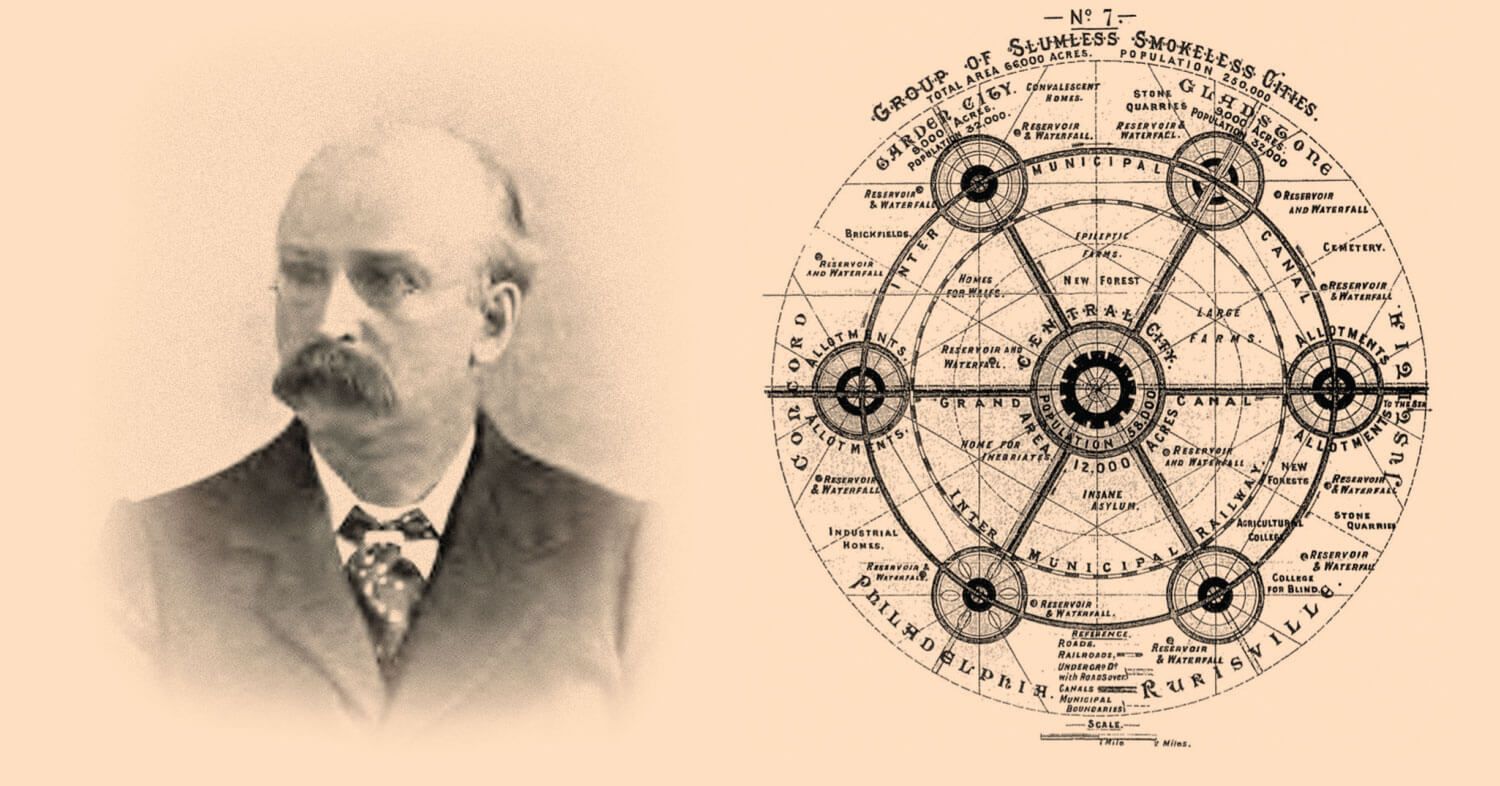

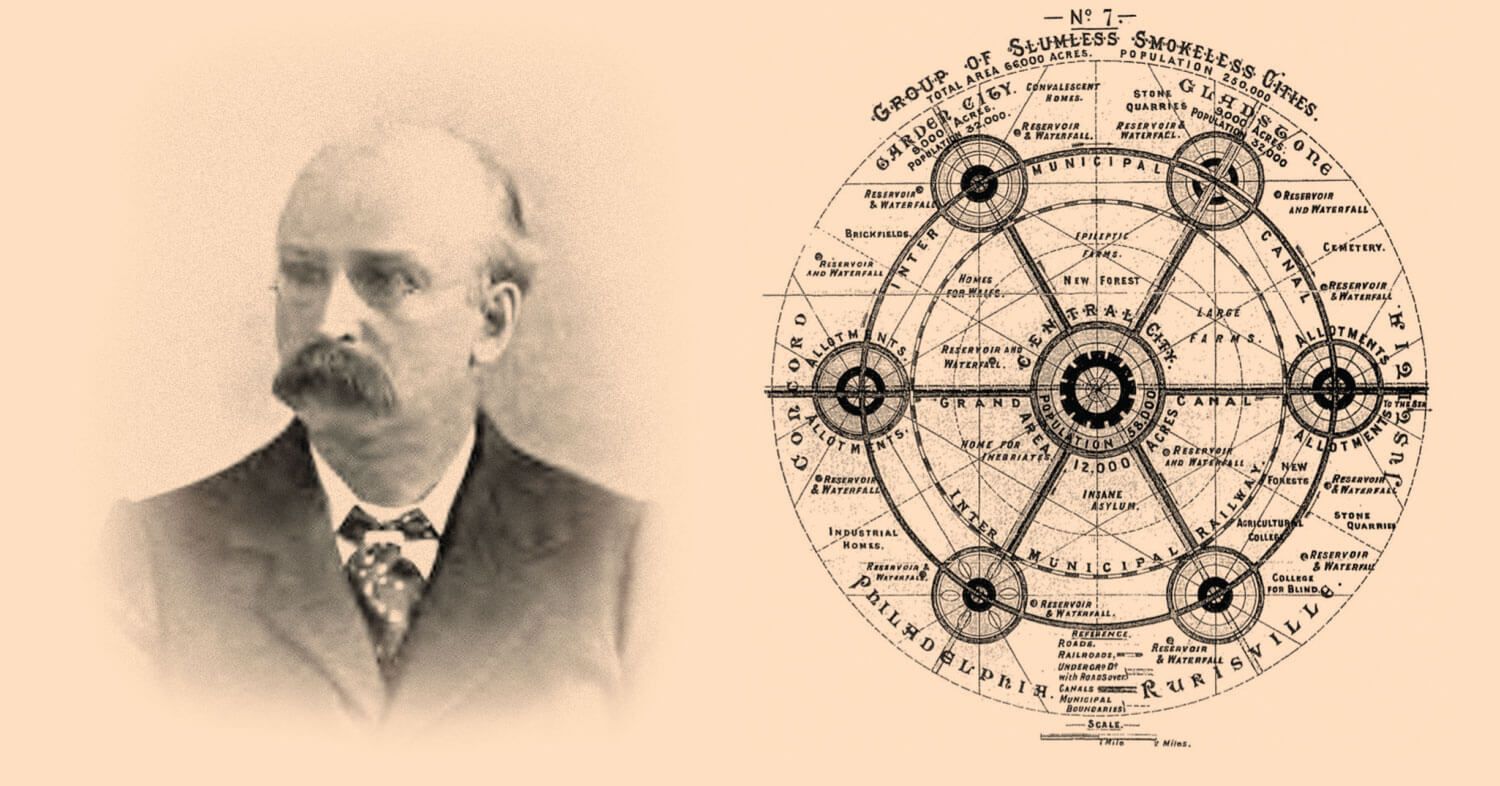

Ebenezer Howard and a diagram of garden cities from Howard’s 1898 book To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform.

Could garden cities help fix these problems? Advocates think so. They argue that garden cities can deliver the humane, sustainable, equitable communities that people want and the planet needs, by slashing emissions, preserving green space, and encouraging neighborly interaction.

Today, garden-city projects are popping up from England to India to Cambodia. In particular, China, where construction rates have exploded since the early 2000s, has become a petri dish for garden cities. Among several planned communities is Heart of Lake, designed by Stern’s firm and currently being built on an island in Xiamen. “We are being asked to do interpretations of it in other Chinese cities,” Stern says.

But many, if not most, of these new garden cities and suburbs will look nothing like Forest Hills Gardens. They will be bigger, taller, and denser. Heart of Lake, for instance, will pack 2 million square feet of construction into a mere 25 acres and include high-rise apartments. It’s also unclear that these projects will adhere to core garden-city values, including community ownership and the mixing of social classes. What’s more, there is little data to prove definitively that garden cities are in fact the right solution for urban ills; firm figures on their environmental, social, and other impacts are hard to come by when no two projects look alike.

In short, the garden city of the 21st century is a slippery concept. Stern says that, in China, getting the government to embrace a new urban form is “like turning a gigantic ocean liner around.” But the real question, it seems, no matter the country, is whether a turn toward garden cities would truly be worthwhile.

In 1898, an unassuming London stenographer named Ebenezer Howard borrowed 50 British pounds to print a short book titled To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. In the book, Howard laid out a plan to arrest the flow of people into great manufacturing centers such as London, whose squalid, disease-ridden slums repelled him. “It is deeply to be deplored,” he wrote, “that the people should continue to stream into the already over-crowded cities, and should thus further deplete the country districts.”

Enter the garden city. Drawing on the political thought of American economist Henry George, who believed the value of land should be common property, Howard described a planned community outside a major city that would combine the social and financial opportunities of the city with the “natural healthfulness” of the countryside. In a handful of simple, concentric-circle diagrams, Howard drew a city that would be home to 32,000 people who would enjoy fresh air, green space, and places to shop and relax. The city would be largely self-contained, with homes, schools, and factories encircled by an agricultural estate.

Howard proposed that a community trust, backed by investors, would buy the land for such a city. Rents collected would fund public improvements and services but would also go toward residents’ gradual purchase of the land. Howard was adamant that this be the case, so that the community could benefit from increases in land value—a principle known as “land value capture.”

Howard had no formal education past the age of 14 and was a classic Victorian tinkerer, but his powers of persuasion were remarkable. By 1903, he had won enough supporters to establish Letchworth Garden City, about 30 miles north of London. Welwyn Garden City would follow years later. Letchworth became the Berkeley of its day, with middle-class progressives moving into its cozy streets. It also attracted industry, which Howard wanted, knowing that a garden city had to provide viable alternatives to work in London.

The idea soon inspired a spinoff. A few years after Letchworth’s birth, a philanthropist named Henrietta Barnett hired that city’s architects to design London’s Hampstead Garden Suburb. The new project shared garden-city ideals, except for self-containment. The garden suburb, as it became known, proved particularly well suited to private development, and the idea spread to the United States, Mexico, Australia, Japan, Egypt, France, and Germany.

There were problems, however. It wasn’t always easy to get motivated groups of backers to establish true garden cities. Moreover, in practice, some ideals were never reached. Howard aimed to provide the poor with quality housing, but Letchworth’s workers’ cottages proved too expensive for many. And the city’s industry, centered on a corset factory, could never really compete with London’s draw. Over time, Letchworth was pulled into the capital’s orbit; today it is home to about as many people as Howard intended, and property values are high (though about half the housing has been made affordable through mechanisms such as reduced rent).

Garden cities and suburbs faded from the scene in the mid-20th century, as Le Corbusier-inspired “towers in the park” came into vogue in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, resulting in a wave of mega-scaled housing projects. It was the age of the automobile too, and compact suburbs became obsolete, while sprawling subdivisions multiplied. More recently, however, sprawl became seen as a menace for, among other things, encouraging people to spew carbon by shuttling around in cars. Tower blocks also fell out of favor, criticized for creating social isolation and breeding crime.

Today, as remedies, some government officials and urban planners in the United Kingdom are resuscitating the idea of garden cities. They see it as an attractive way to deploy green technologies, such as high-performance buildings and clean mass transit, while addressing the country’s housing shortage. (In England, between 2001 and 2011, 1.4 million homes were built, while the country’s population increased by almost 4 million).

This year, the United Kingdom’s Wolfson Economics Prize will award £250,000 to the entrant with the best proposal for a “new Garden City which is visionary, economically viable, and popular.” Five finalists were selected from 279 entries, in anticipation of a Sept. 3 announcement of the winner. One uses financial modeling to show how a small garden city would be feasible; another proposes doubling the size of an existing urban locale along garden-city lines.

In April, British Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg announced that the government would accept bids to construct up to three new garden cities. “[W]e need to create planned communities: whole new towns with the infrastructure and amenities they need, communities where people genuinely want to live, and built where demand is high,” Clegg wrote in the Daily Telegraph in January. The garden cities will have at least 15,000 homes each. Their sites have not yet been chosen, but they will likely be in southeastern England. Separately, the government has said it wants to build another garden city at Ebbsfleet, in Kent.

Some critics argue that the fuss around garden cities obscures the real problem: the scarcity of housing in and around London, the European Union’s most populous metropolitan area. Urban redevelopment would accomplish more than building new garden cities ever could, according to Alexandra Jones of the nonprofit group Centre for Cities. “You might not have objections to a garden city in the middle of nowhere, but you might not have demand to live there either,” she wrote in June on the website Planning Resource, calling garden cities “the flavour of the month.” Critics also take issue with the relatively low density of the garden-city model, saying it will consume too many resources and actually promote car use by spreading out development.

The government is determined to reassure citizens of garden cities’ benefits and may even offer people tax breaks to accept construction near their homes. Still, local opposition and bureaucratic red tape could stymie development for some time. Meanwhile, Howard’s big idea has already found new life in other corners of the globe, including China. It’s here, however, that the promise and potential pitfalls of the garden city’s renaissance are most glaringly juxtaposed.

The cover of Paradise Planned by David Stern, and an aerial photo of Jardim America — a community planned around the garden city concept— on the outskirts of Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Garden cities may take root in China widely for a number of reasons—not least among them the rapid growth of cities that are a step down in size from the likes of Beijing and Shanghai. The government’s new urbanization plan, released in March, seeks to route rural migrants away from “extra-large” cities and toward smaller ones. Whereas cities expanded spatially in the 1990s and 2000s, “what we will see going forward is a reversal,” says Jonathan Woetzel, a McKinsey analyst in the country. “China will move toward a denser model,” with more hub cities and satellite towns, connected by railway and highway infrastructure.

The cities of Chengdu and Chongqing in southwestern China have been designated as special testing zones for urban-rural integration strategies. And, perhaps noting similarities between the country’s urbanization goals and Howard’s vision for turn-of-the-century England, local leaders are looking to garden cities for guidance. Chengdu officials traveled to London in November 2013 to meet with the Town and Country Planning Association (tcpa), the latter-day incarnation of the Garden City Association, founded by Howard in 1899. They also toured Letchworth.

Meanwhile, private developers are already putting the garden-city concept into practice. On the outskirts of Chengdu, development parcels are being sold for Tianfu Ecological City, designed by the Chicago firm Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture (better known for its towers in Dubai and Abu Dhabi) and funded by Beijing Vantone Citylogic Investment Corp., a real estate company focused on sustainable urban development. Howard said a garden city should occupy about one-sixth of the property in an overall project; most of the area should be devoted to green space. Likewise, structures in Tianfu will take up one-seventh of its whole site, Gill said, and a “buffer landscape” will surround them to conserve farmland and prevent sprawl. Tianfu’s master plan even has the telltale concentric pattern of Howard’s diagrams, with a green zone at its heart.

Similar projects are spreading. Wei Yang, a Chinese-British urban designer whose firm specializes in garden-city plans and is a Wolfson Economics Prize finalist, recently won a commission to coordinate garden-city planning in Jiangsu province, and her firm has created two master plans for Hunan province. (Yang has also been detailed by the British government to advise China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development on sustainable urbanization.) Other garden-city-inspired projects include Heart of Lake and Gai Lan Creek in Chongqing, both designed by Stern’s firm, and Yuelai Eco-City in northern Chongqing, planned by the California firm Calthorpe Associates.

But just how closely will these ventures follow Howard’s guidelines, set more than a century ago? Not very, by early indications—raising the obvious question of whether the projects can even be called garden cities.

Take the issue of density. Once full, Tianfu will pack 80,000 people into a thicket of apartment buildings. That’s more than twice as many inhabitants as Howard imagined in a location one-third the size. Additionally, Tianfu won’t have a separate zone for industry. Rather, apartments will sit next to, and even on top of, offices and shops—a mixed-use model becoming more common in China.

Then there is the matter of residential control of land. Chinese land is government-owned, and Yang explains that local authorities typically buy farmers out of their leases in order to build new towns and cities. This is often done with lump sums of cash. If garden-city projects did something different—for instance, set up trusts for long-term management, with residents as stakeholders—it would be a “policy breakthrough,” Yang says, helping foster a fresh spirit of community engagement among new arrivals to China’s urban communities. But local governments would have to accept the idea of trusts, which is anything but guaranteed.

An additional tripping point is socioeconomic balance. The plans for Tianfu call for integrated affordable housing, a rarity in China, where low-income housing is usually isolated from other habitations. But Gordon Gill, one of Tianfu’s main designers, admits there is nothing to hold the developer to that goal. (After all, the developer is, like any other, eager to make a lot of money.)

On top of everything, there are common failures in Chinese urban planning to which garden cities could fall victim. Buildings are often constructed at warp speed, and designs aren’t always followed closely, leading to shoddy end products. Moreover, China’s famous “ghost cities” testify to the folly of assuming that if you build it, they will come. Without nearby jobs, Woetzel says, new cities will have a hard time attracting newcomers, even among the up-and-coming middle class.

Certainly, China isn’t alone in posing problems that could undermine garden cities as they were intended to be. Two thousand miles away from Chengdu, in the Indian city of Ahmedabad, residents have moved into the first phase of Godrej Garden City, which will house 5,000 people and feature bike lanes, parks, and rapid mass transit. Here “garden city” is partly a marketing moniker: Residents won’t own the land, and the target buyers are middle- and upper-middle-class people who may own more than one car. (The project manager emphasizes, however, that hundreds of units are planned for lower-income residents.)

Back in the United Kingdom, Clegg’s prospectus for new garden cities mentions tcpa principles, which are rooted in Howard’s 1898 treatise, but it doesn’t make them binding. “The Government does not wish to impose any definition of what Garden Cities are, but instead intends to work with localities to support them in developing and delivering their own vision,” the prospectus reads. There are no required affordable-housing minimums either, though the tcpa has recommended that at least 60 percent of housing be discounted from market rates.

The risk, ultimately, is that these new projects could wind up lacking the whole package of qualities meant to set garden cities apart. Some who support the revival of Howard’s idea, however, seem to think this doesn’t much matter—or at least seem willing to live with compromise.

Renderings and plans by design architects and master planners Adrian Smith and Gordon Gill, for Tianfu Ecological City, which will be located on the outskirts of the Chinese city of Chengdu.

It was virtually inevitable that, with the explosion of the global population, the size and shape of garden cities would change; otherwise, the concept would likely be wholly disregarded as quaint and impractical. And there are many ways in which new projects demonstrate Howard’s principles—perhaps not all of them simultaneously, and perhaps not as precisely as possible, but still in such a way as to reap important social, environmental, and other benefits.

“Moving more towards transit, walking, and biking is what has to happen, but you can’t do that without the right urban form. It’s a critical pivot point,” says Peter Calthorpe, the principle of Calthorpe Associates. What’s more, he adds, “when you have a superblock of 5,000 units, people don’t know each other. You go to a walkable city block—500 units a block—and all of a sudden you can know your neighbor again.”

Indeed, walkability is a Howard-approved feature emphasized in many of today’s garden cities. Walkable neighborhoods have been shown to have higher social cohesion, lower levels of obesity and diabetes, and lower rates of driving. And China, in particular, is a place where the feature could do a lot of good. Nearly 140 million passenger cars are on the road now, and the number could reach 500 million or higher by 2040. There’s an opportunity, however, to design cars out of new developments, or at least from residents’ day-to-day mobility. Most Chinese still don’t have vehicles, and between 50 and 60 percent of trips in cities are still by foot or on bicycles. “There’s a window, as we think about the planning of these things, to influence the energy usage per capita,” McKinsey’s Woetzel says.

To that end, Heart of Lake will have pedestrian-only streets. Every point in Tianfu will be reachable within a 15-minute walk, reducing the need for cars, and a transit center will connect it to Chengdu. (Tianfu’s creators project that the city overall will use 48 percent less energy than a similar, conventional development and generate 60 percent less carbon dioxide.)

Similarly, modern science is corroborating Howard’s zeal for the restorative power of green space. A recent study estimates that trees prevented about $7 billion worth of health problems in the United States in 2010 alone, and researchers in Scotland have found that living near greenery helps close the “health gap” between the rich and poor. Today’s garden cities generally prioritize green space: Godrej Garden City, for instance, will have a central park and other small ones, while 15 percent of the land in Tianfu is reserved for green areas.

To be sure, evidence of garden cities’ benefits is oblique, drawn from studies on particular variables in many urban settings. Recognizing this deficiency, the tcpa has highlighted the need for focused research on planned communities. Some critics, meanwhile, are asking why it wouldn’t be better, say, to stitch new parks into existing metropolises, lay bike lanes down busy avenues, and redevelop vacant sites, rather than build entirely new locales.

Such piecemeal redevelopment has limitations. It’s difficult to coordinate, for example, and it relies heavily on existing infrastructure, good or bad. Master planning of new cities, by contrast, can address many needs at once—and from a clean slate and for a lot of people. It’s no coincidence that the initial push for garden cities arose in an era when many thousands of Britons lived in cramped slums for lack of adequate housing, while others yearned for peace and quiet that London could not provide. Similarly, today millions of Chinese are seeking places to live and economic opportunity, while others want a more comfortable, middle-class existence. Garden cities, proponents point out, allow planners to place large numbers of these people in places that, from scratch, can concentrate on what has been shown to make cities both healthy and efficient.

This isn’t to say that garden cities and urban renewal should be mutually exclusive. Rather, they could be part of a two-pronged urban development strategy, sharing similar features. “The simple answer is that we need both,” Katy Lock, a tcpa advocate, wrote in an email. “The scale of the crisis means that we can’t meet our needs on a plot-by-plot basis alone.… A new community provides opportunities for holistic planning and the economies of scale to truly embed the principles of sustainable development.”

George Hoban, a 17-year resident of Forest Hills Gardens, lives on the central square in a former inn that is now a co-op apartment building. It is clear from Hoban’s description of his neighborhood, offered on an impromptu tour on a sunny July day, that the place isn’t exactly what Ebenezer Howard had in mind. Property values can top $4 million, and there’s no greenbelt or anchoring industry. Yet Hoban reels off local attractions that sound familiar: The Long Island Rail Road is on-site; the subway is two blocks away; young families can get by without a car; and Hoban lives in an affordable, one-bedroom apartment just a stone’s throw from a mansion.

“If I turn right from my building, I’m in the suburbs. If I turn left, I’m in the city,” Hoban says. When people arrive in the neighborhood for the first time and admire its aesthetic, he adds, “it gives me a great deal of pride to live here.”

Perhaps a pure garden city, pulled straight from the pages of To-morrow, has never existed and never will. But even when shrunk down from Howard’s utopian ambitions, garden cities still hold the potential to make crucial contributions to the planet and to people’s lives.

Discussing the value and urgency of his work, Gordon Gill mentions The Machine in the Garden by Leo Marx. The book wrestles with the tension between technology and the pastoral ideal, and Gill says it reflects the fact that, for a long time, many people yearned to escape the machine (the city) for the garden (the country). But no longer.

“The machine itself,” he insists, “has to become a garden.”

Tianfu images courtesy of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture. Paradise Planned images courtesy Monacelli Press.

FUTUR team

This blog and news section of our website is a platform for our FUTUR Community to create safe and brave space for engagement, inspiration, sharing of resources, ideas, articles, content, etc. Thanks for reading!